About the Reichard, Nicodemus, Miyal materials: Texts, Grammar, Stem List, Affix List

Texts and Grammar

The unpublished field notes and typed manuscripts of Coeur d'Alene myths and tales presented in this archive were recorded in 1927 and 1929 by Gladys Reichard. The COLRC contains a biographical sketch of Reichard by Julia S. Falk, used by permission, that you can access here ---**Link**----[link to Falk]. The texts, or narratives, cover what Reichard classified into "myths and tales" and "tales with historical elements". The "myths and tales" are further divided into "Coyote cycle" and "myths not in Coyote cycle." She notes in her English translation (Reichard 1947:5-6) in the collection there are... the following regarding the narratives:

In this collection there are thirty-eight myths, that is, accounts of things as they happened before the world was as it is now; two tales or accounts of happenings in the historical period; and ten narratives of actual historical encounters which were remembered by living people or which happened not less than a hundred years ago.

The numbering of each text in the COLRC follows numbering of Reichard 1947 (cf. Figure 1 below) directly preceding the title. The unpublished manuscripts are numbered in accordance with Reichard's written number on each manuscript and the same is true of the fieldnotes (cf. Figure 2 below).The COLRC includes the Reichard 1947 number in the COLRC identifier for each narrative in its various forms (e.g. unpublished manuscripts, fieldnote, or audio recordings). In addition, the titles reflect Reichard 1947 and may differ from titles on field notes and typed manuscripts (see metadata for cross referencing).

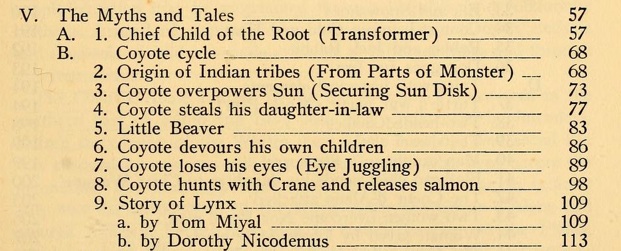

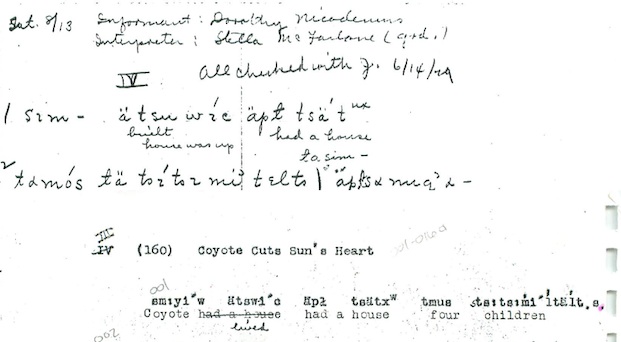

In Figure 1 below we see an excerpt from the table of contents of Reichard 1947 where each narrative/text is given a number. This is the number used in the COLRC identifier and the number give to the narrative in the list of narratives in the COLRC. In Figure 2 we see a screen shot of 'both' field notes and typed manuscript for Coyote overpowers Sun (Securing Sun Disk). This is narrative number 3 in Reichard 1947 and in the texts list in the COLRC. However, while the fieldnote includes the roman numeral IV, the typed manuscript page includes the roman numeral four which we can see has been struck through and replaced with the roman numeral III. This suggests that Reichard reorganized the narratives in her final publication of the English translations.

Figure 1 from 1947 Table of Contents

Figure 2 fieldnotes and typed manuscript

Reichard notes that some of the narratives were given no titles by the narrators. In such cases she chose a title that reflected the content of the narrative. Published English translations of each narrative/text, can be accessed by selecting the 'Published English Translation' link. This link will take the viewer to the pages of 'An Analysis of Coeur d'Alene Indian Myths' (Reichard 1947) found at the Internet Archive where the narrative translation can be found.

The 1917 publication of Teit's Coeur d'Alene "tales" which include different versions of a small number of the Coeur d'Alene texts recorded by Reichard, and which Reichard makes reference to in her 1938 grammar, can also be found online at the Internet Archive.

The narratives provided here were collected from photo-copies of Reichard's original manuscripts and the quality varies from text to text. Files are available for download in PDF form or as PNG files within the website. The list of complete narratives can be found herehere.

The Foreword to Reichard's 1938 grammar of Coeur d'Alene, sheds some light on how the data was collected. It is worth quoting at some length.

The material presented in the Grammar of the Coeur d'Alene Language, together with a body of texts, was obtained on two field trips in the summers of 1927 and 1929 in Northern Idaho. These trips were made possible by grants from the Committee for the Study of Indian Languages, [and] Council of Learned Societies...In 1935 and 1936 it was possible to have Lawrence Nicodemus, a young Coeur d'Alene man, at Columbia University where the study was continued. The Columbia University Council for Research in the Humanities through a grant, made it possible to continue the work...

The source of the texts was twofold. Stories were obtained from Dorothy Nicodemus, widow of Teit's chief informant...and from Tom Miyal. Dorothy's daughter-in-law, Julia Antelope Nicodemus, cooperated in grammatical analysis in a most interested and stimulating way. Not only did she do all in her power to help, but she encouraged her son Lawrence to learn to write. It is to him I owe such careful phonetic differentiations...and other fine distinctions, which have since turned out to have grammatical and historical significance. Interest such as that displayed by Julia and Lawrence make this kind of work, not only a great satisfaction in itself, but add to it rare pleasure.

Besides the cooperation of the Coeur d'Alene, I have had during the long period of my study, the constant, encouraging, and never-failing stimulation of discussion and help from Professor Franz Boas. From the field where he was recording Chehalis, I had frequent letters with guiding notes during my first year with the Coeur d'Alene. Since then he has never been so deeply immersed in his own studies that he could not be induced to discuss patiently a moot point in Salish, or to serve as critical audience before whom to clarify a point. Furthermore, he has placed at my disposal his own massive material.

In her 1947 English translation of the narratives, Reichard provides greater detail regarding her collaborators from the Coeur d'Alene community. In chapter 2 of the volume she describes her work with Dorothy Nicodemus and Tom Miyal, her primary narrators. Brinkman (2003) provides further insights into the working relationships of the team that produced and analyzed the narratives and the setting in which the narratives were recorded. Brinkman notes (p.c.) that "Dorothy Nicodemus" actually appears as "Dorthy" on her tombstone. We do not make the change here for consistency with the names as they appear in relation to the Reichard materials. In addition he also notes that "Tom Miyal" was also known as "Tamiyel". Again, we do not change the names as Reichard produced for consistency and clarity in regards to the body of work, but feel it is important these facts be noted.

Page 2 of the 1947 English translations describes Julia Antelope Nicodemus' contribution to the project. Again, it is worth quoting in some detail.

I was fortunate in making the acquaintance of Mrs. Julia Antelope Nicodemus who was one of these [those that value their culture]. She was the daughter-in-law of Teit's chief informant, Nicodemus, and his wife, Dorothy, my informant. Julia did everything in her power to aid me in my work, for she quickly comprehended the problems of linguistic analysis and was greatly intrigued by them. Her work as interpreter is obvious in the translations...and grammar and, not only did she furnish all possible information of which she herself was possessed but she referred more difficult matters to her mother, Susan Antelope, and her brother, Maurice Antelope, with whom I did not work directly. She encouraged her son, Lawrence, to come to New York a few years later when he collaborated in the work of preparing the grammar. Without Julia's thorough understanding of the task and her valuable advice as to ways to going about it my results both linguistic and mythological would have been much more scanty.

The two chief narrators, Dorothy Nicodemus and Tom Miyal, are described in Chapter II. Julia was my interpreter for their tales. She learned to write Coeur d'Alene and contributed the historical narrative Nos. 42 and 46, as her own compositions written in Coeur d'Alene.

Reichard has the following to say regarding Tom Miyal one of her primary informants when discussing plot in the narratives (Reichard 1947:6-7).

There are elements which have nothing to do with plot [in the narratives], such as the touches which a lively narrator like Tom Miyal introduces for the sake of humor. Waterbird sticks the handkerchief given him by the chief's daughter into his coat pocket so that one corner shows. This element merely verbalizes a human conceit. The Land People phone up river to Snake. This is an amusing reference to the way white people do things. There are other modernizations which seem like purely stylistic elements but which have additional significance. For instance Waterbird became a dishwasher through shame at forgetting his appointment with the chief's daughter.

Later she describes her primary narrators as follows (Reichard 1947:33).

Dorothy Nicodemus was the widow of Nicodemus who gave Teit most of the material in his Coeur d'Alene ethnology. Nicodemus died many years ago. Dorothy was an eager and interested student of his lore, she had a good memory and took great pride in her own knowledge. She was over seventy at the time the tales were recorded and her own experiences alone provided much of interest. Some of them were bitter, but she had a kindly temperament and a sweet disposition. As a result she was frequently exploited. During the last few years she gradually became totally blind and was consequently quite dependent upon others. She managed however to catch muskrats in her brook, to cook for herself and for her sons and grandson when they were home and to perform other necessary tasks. She enjoyed company and loved to tell stories. All the acts of the tales were graphic and alive to her and by intonation and gesture she added much to the intrinsic nature of the style. I have mentioned before her habit 'a bad one from our point of view' of using 'like this he did,' the simile depending upon gesture and act rather than upon words. She preferred to retain old forms in her tales and almost never consciously brought in modernities. She could explain some phrases only by saying, 'It belongs to the story.' She was just as conservative in her outlook on life. Spiritually she belonged to the days when the Coeur d'Alene possessed and used the rivers, lakes, forests and prairies as fishing, hunting and digging grounds. Her style reflected this attitude and nothing materially or even intangibly modern changed it. Her humor was quiet but copious. She appreciated a joke with the best and she had many at her tongue's end.

Tom Miyal was a nice contrast to Dorothy. His humor was active and continuous. Everyone expected a joke from Tom, even if he was seen for only a moment on the street or in passing. In a gathering a running stream of wisecracks was expected from him. He was invariably good-tempered and it was said that he could always be depended upon to make fair judgments. Some of these characteristics were reflected in his versions of the myths. Wit is the outstanding difference between his and Dorothy's. Hers are humorous, whimsical; his, sparkling, ridiculous. One way in which he attained his effects is through the use of modern elements. He has the Land People 'phone' upriver to make a trap for Snake...His vocabulary, which can be ascertained only by a detailed comparison of texts, differs considerably from Dorothy's, and he was able by changing tone and accent, to make the use of foreign phrase even funnier than they ordinarily sounded.

The recorded texts do not do justice to his style. He was primarily concerned with movement, with action, with the development of the myth. He had no conception of the slowness of some white recorders and often had to be slowed down. Consequently some of his phrase are lost.

Other than Reichard's own work (esp. 1938 and 1947), Raymond Brinkman's excellent dissertation on Lawrence Nicodemus (Brinkman 2003) provides informative discussion regarding Reichard, the Nicodemus family, and the recording of the narratives. In addition, Julia Falk provides two outstanding works (Falk 1999, Falk 1997) detailing the life work of Gladys Reichard with discussion of her work with the Coeur d'Alene, which is viewed by Salishan scholars as excellent.

Stem List

The stem list was originally published by Reichard in the International Journal of American Linguistics volume 10 numbers 2/3 1939. In 2009 Shannon Bischoff and Musa Yasin-Fort created a facsimile of the original article using text files, HTML, Unicode fonts, and the Salishan and Nicodemus orthographies. The change from Reichard's orthography to the Salishan and Nicodemus orthographies include conventions for representing certain phonological content such as what have been referred to as echo vowels. In this way the facsimile is in part interpretation. The text files where updated by Amy Fountain to HTML4 in 2012. A copy of the original article, now in the public domain, can be found in the COLRC here----****[link to original article]****----. In his 1966 PhD dissertation Sloat re-analyzed Reichard's vowels and spelling to arrive at a Generative Phonological account of each entry and thus a different spelling for most stems based on interpretation of vowels in the original publication by Reichard.

Affix List

The affix list was created by Shannon Bischoff and Musa Yasin-Fort in 2009 using text files, HTML, and Unicode fonts. The text files where updated by Amy Fountain to HTML4 in 2012. The affixes were taken directly from Reichard's grammar and simply listed in alphabetical order in corresponding categories to those in Reichard's grammar. Each entry contains a link to the original entry found online in Reichard's grammar at the Internet Archive. The entries are in the Salishan and Nicodemus orthographies. Changes from Reichard's orthography to that of the Salishan and Nicodemus include minor changes to forms that reflect contemporary representation of certain phonological elements.

Orthographies

There are three orthographies found in the COLRC. These are what are referred to as the Reichard orthography (the orthography used by Gladys Reichard), the Nicodemus orthography (the orthography used by Lawrence Nicodemus and the Coeur d'Alene Tribe), and what Lyon and Green-Wood (2009) referred to as the Salish orthography (that used by the Salish scholarly community). Barthmaier's (1996) algorithm for going from Reichard's orthography to the Salish orthography was used to render materials originally in Reichard's orthography to that of the Salish orthography. Lyon and Green-Woods algorithm for going from the Nicodemus orthography to the Salish orthography was used to render Reichard's orthography, once in the Salish orthography via Barthmaier's algorithm, to Nicodemus' orthography. In addition, certain changes in representation were made to capture contemporary practices in the representation of certain phonological phenomena.

References

Barthmaier, Paul T. 1996. A dictionary of Coeur d'Alene Salish from Gladys Reichard's file slips. University of Montana M.A. Thesis.

Brinkman, Raymond. 2003. Etsmeystkhw khwe snwiyepmshtsn 'you know how to talk like a whiteman'. University of Chicago Ph.D. Dissertation.

Boas, Franz, and Teit, James. 1985. Coeur d'Alene, Flathead and Okanogan Indians. Ye Galleon Press: Fairfield, Washington. Reprint of the Annual report of the Bureau of American Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution volume 45 (1927-28) pages 23-396.

Falk, Julia S. 1997. Territoriality, relationships, and reputation: The case of Gladys A. Reichard. Southwest Journal of Linguistics 16.1/2.

Falk, Julia S. 1999. Women, Language, and Linguistics: Three American Stories from the First Half of the Twentieth Century. Routledge: London.

Lyon, John and Rebecca Greene-Wood, eds. 2007. Lawrence Nicodemus's Coeur d'Alene dictionary in root format. UMOPL

Reichard, Gladys A. 1938. Coeur d'Alene. Franz Boas, ed., Handbook of American Indian languages. New York: J. J. Augustin, Inc. Part 3:515-707.

Reichard, Gladys A. 1939. Stem-list of the Coeur d'Alene language. IJAL 10:92-108.

Reichard, Gladys Amanda with Adele Froelich. 1947. An analysis of Coeur d'Alene Indian myths. Philadelphia: Memoirs of the American Folk-lore Society, v. 41.

Sloat, Clarence. 1966. Phonological redundancy rules in Coeur d'Alene. University of Washington PhD dissertation.